Beyond the Trip: The Science of Psychedelic Therapy

- Larrie Hamilton, MHS

- Jul 27, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 31, 2025

The science behind psychedelic-assisted therapy, how these substances work in the brain, the rigorous clinical process involved, and the evidence-based potential for treating complex mental health conditions.

| Psychedelic therapy is being reimagined not as a fringe experiment, but as a data-backed, clinically integrated approach to healing. Researchers are pairing compounds like psilocybin and MDMA with structured psychotherapy, showing that even a single session can catalyze profound emotional breakthroughs. |

Takeaways

Psychedelic therapy is a highly structured process combining a potent drug with intensive therapy.

These compounds work by temporarily dissolving the brain's rigid, predictive models of reality.

The primary therapeutic mechanism appears to be a lasting change in a person's core sense of self.

Safety is paramount, involving rigorous screening to exclude individuals with a history of psychosis.

Current peer-reviewed evidence does not support the benefits of microdosing for mental health.

A Sober Look at Psychedelics: The Data on a New Therapeutic Frontier

As a medical scientist, my work is grounded in data, process, and evidence. For years, the class of substances known as psychedelics existed far outside the bounds of conventional medical research. They were seen as unpredictable, dangerous, and without therapeutic merit. But over the past two decades, a quiet revolution has been taking place in some of our most respected research institutions.

Scientists are now applying the full rigor of the scientific method to these compounds, and the data emerging is compelling. We are beginning to understand not only that they can work for some of our most stubborn mental health conditions, but how they work. This isn't about magical thinking; it's about neurobiology, psychology, and a highly structured therapeutic process. My goal here is to walk you through the science of what we know today.

What Makes a Substance "Psychedelic"?

The term "psychedelic" covers several different types of substances, but they all share one core characteristic: the ability to profoundly alter a person's perception of reality, consciousness, and their own sense of self. They are not a single class of drug but are generally grouped into three main categories in a therapeutic context:

Classic Psychedelics: This group includes psilocybin (from mushrooms), LSD, DMT, and mescaline. Their primary mechanism of action is targeting the brain's serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptors.

NMDA Antagonists: Substances like ketamine and PCP fall into this category. They work on a different system, blocking the brain's NMDA receptors, which are involved in learning and memory.

Entactogens: This is a unique class primarily defined by MDMA. The term means "touching within," as it tends to foster feelings of empathy, connection, and emotional openness rather than the intense perceptual changes of classic psychedelics.

How These Compounds Appear to Work in the Brain

For most of our lives, our brain operates on autopilot. It builds predictive models to help us navigate the world efficiently. You don't consciously analyze every single visual cue to recognize a chair; your brain predicts "chair" based on past experience. This efficiency, however, can become a prison in conditions like depression or PTSD, where the brain is locked into rigid, negative patterns of thought and prediction.

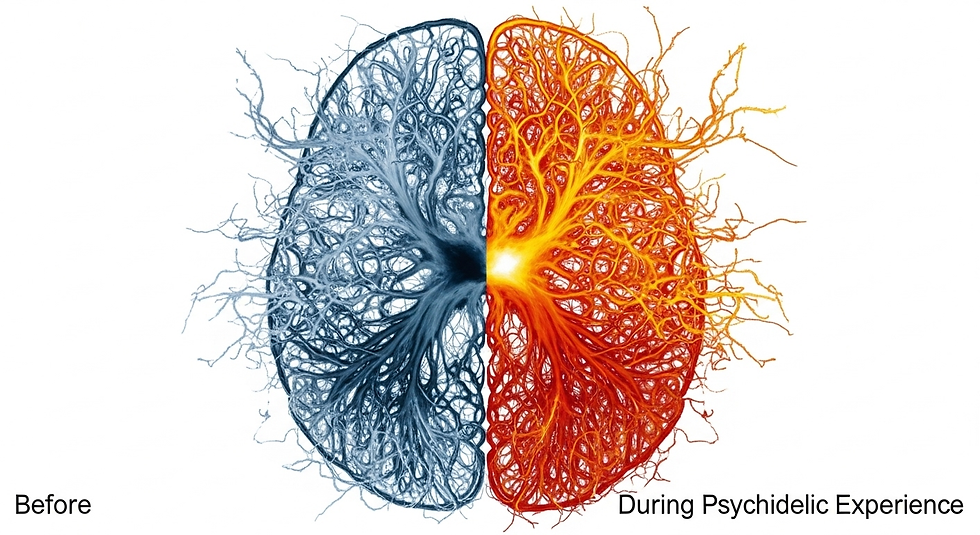

Psychedelics appear to work by temporarily dissolving these predictive models. They reduce the influence of the brain's "default mode network," a hub of self-referential thought. The result is what researchers call "dis-habituation"—the ordinary can suddenly seem extraordinary. It's like rebooting a computer that has become bogged down by old, inefficient software. This state allows a person to step outside their rigid thought patterns and observe their own life and experiences from a new, objective viewpoint.

Real-Life Example: A patient in a smoking cessation trial at Johns Hopkins, a long-time smoker, described looking at a cigarette during his psilocybin session and seeing it for what it was: a cylinder of paper filled with dried leaves. The web of emotional attachment, habit, and craving was temporarily gone. He saw the object itself, and it lost its power over him.

The Therapeutic Process: A Structured Journey

This is perhaps the most misunderstood aspect of psychedelic medicine. The therapeutic benefit does not come from the drug alone; it comes from the combination of the drug with a carefully managed psychological process.

Therapeutic Use | Recreational Use |

Goal: Healing, Insight | Goal: Entertainment, Escape |

Setting: Controlled, Safe | Setting: Unpredictable |

Guidance: Trained Professionals | Guidance: Peers or None |

Safety: Medical Screening | Safety: No Screening |

Outcome: High potential for lasting benefit | Outcome: Unpredictable, higher risk of harm |

Rigorous Screening: The first step is to ensure patient safety. This is not for everyone. Individuals with a personal or family history of psychotic disorders (like schizophrenia) or bipolar mania are excluded, as the experience could trigger a lasting psychiatric crisis.

Extensive Preparation: Patients spend hours with two trained therapeutic guides in the weeks before the session. This builds a deep sense of trust and rapport. They discuss the patient's life history, intentions for the session, and what to expect.

The Session: The session itself takes place in a controlled, comfortable environment, often resembling a living room. The patient takes a high dose (e.g., 20-30mg of psilocybin), lies down on a couch, wears an eye mask, and listens to a curated playlist of music. The guides are present for the entire 6-8 hour experience, offering reassurance but rarely intervening. Their job is to hold a safe space.

Integration: In the days and weeks following the session, the patient meets with the guides again to "integrate" the experience—to make sense of the insights, emotions, and memories that came up and translate them into lasting change.

Even in these ideal clinical settings, studies report that about one-third of participants experience some form of significant psychological distress—a "bad trip." The therapeutic advice is consistent: don't fight the experience.

The Core Mechanism: A Lasting Shift in Self-Representation

So why does this process lead to lasting change? The evidence points to a fundamental shift in "self-representation"—how a person views themselves and their place in the world. Many mental health conditions are rooted in a rigid, negative story we tell ourselves ("I am worthless," "I am broken," "The world is unsafe").

The psychedelic experience seems to provide the distance to see that this story is just that—a story, not an immutable fact. Patients often describe having "duh experiences," simple but profound realizations that they have the power to change their lives. This sudden feeling of agency can break the cycle of depression, addiction, or trauma.

A Cautionary Note on Microdosing

While the data on high-dose therapeutic sessions is robust, the same cannot be said for microdosing (taking tiny, sub-perceptual doses). Despite anecdotal reports, the current body of peer-reviewed, placebo-controlled evidence shows no significant benefits of microdosing for depression, anxiety, or cognitive enhancement. Some studies even suggest it may slightly impair cognitive function and time perception. More research is needed, but for now, the hype has outpaced the data.

The Future: Neuroplasticity and Brain Repair

The research is still in its early stages, but the future is promising. One of the most exciting avenues is the potential for psychedelics to promote neuroplasticity—the brain's ability to form new connections and repair itself. Early-stage research is exploring whether these compounds could help treat conditions like traumatic brain injury (TBI) in athletes or aid in recovery from stroke.

Final Thought

Psychedelic compounds are not a panacea. They are powerful tools that, when combined with a rigorous therapeutic structure, appear to hold significant potential for treating some of our most challenging mental health conditions. The key is the process. It's the combination of the right patient, a safe environment, trained guidance, and a potent biological agent that allows for these profound shifts to occur. This is not a shortcut, but rather a deeply intensive process that may open up new doors for medicine and mental wellness.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is this the same as using psychedelics recreationally?

No, they are fundamentally different. Therapeutic use involves extensive screening, preparation with trained guides, a controlled setting, a specific dose, and post-session integration therapy. Recreational use lacks all of these safety structures and presents far greater psychiatric risks.

Is psychedelic-assisted therapy legal?

For the most part, no. MDMA and psilocybin are currently only legal within approved clinical trial settings in the U.S. and most other countries. Ketamine is an exception and can be legally prescribed for depression in clinical settings. Regulatory approval for MDMA and psilocybin is anticipated in the coming years, but they are not yet available to the general public.

What are the biggest risks involved?

The primary risk is psychiatric destabilization in vulnerable individuals, which is why screening for psychosis and bipolar disorder is so important. The other main risk is a "bad trip," a period of intense fear, anxiety, or paranoia during the session. While distressing, these experiences are rarely lasting when managed in a therapeutic setting.

How long do the therapeutic effects last?

This is a key area of research, but current data is promising. Studies on psilocybin for depression and anxiety have shown that a significant percentage of participants maintain benefits at 6-month and even 12-month follow-ups after just one or two sessions, which is dramatically different from conventional daily medications.

Can these substances be addictive?

Classic psychedelics like psilocybin and LSD are not considered addictive in the same way as substances like opioids or alcohol. They do not typically cause compulsive use or physical withdrawal symptoms. MDMA and ketamine carry a higher potential for abuse, though still lower than many conventional drugs.

Sources

Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Goodwin, G. M. (2017). The Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic Drugs: Past, Present, and Future. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(11), 2105–2113.

Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Carducci, M. A., et al. (2016). Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(12), 1181–1197.

Ona, G., & Bouso, J. C. (2020). The challenging experience with psychedelics: A narrative review of the scientific literature. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology,

Schenberg, E. E. (2018). Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and Development. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 733.

Vollenweider, F. X., & Kometer, M. (2010). The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(9), 642–651.

About Larrie Hamilton, BHC, MHC

As a medical scientist, I combine research expertise with a passion for clear communication at BioLife Health Research Center. I investigate innovative methods to improve human health, conducting clinical studies and translating complex findings into insightful reports and publications. My work spans private companies and the public sector, including BioLife and its subsidiaries, ensuring discoveries have a broad impact. I am dedicated to advancing medical knowledge and creating a healthier future. Follow me on LinkedIn.