The Connected Brain: A Blueprint for a Happy Life

- David Priede, MIS, PhD

- Jul 25, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Sep 11, 2025

The longest study on happiness reveals a surprising truth: your relationships are literally wiring your brain for health and longevity. Discover the neuroscience behind connection, stress, and well-being.

| Your strategy for a happy life is probably wrong; 85 years of data prove it. This article is a strategic brief on what builds lifelong well-being. Ignoring this information is a profound strategic error. |

Table of Contents

Abstract

This article combines valuable insights from the Harvard Study of Adult Development, the longest-running longitudinal study of human life, with findings from contemporary neuroscience. Its goal is to explore the neural mechanisms that contribute to long-term well-being, enhancing our understanding of what truly supports happiness and fulfillment over time.

From a neuroscientific perspective, this research suggests that the significant impact of relationships is mediated by their ability to regulate physiological stress responses, foster neuroplasticity, and optimize brain health throughout life. We will examine how chronic social isolation and toxic relationships can increase allostatic load, lead to neuroinflammation, and accelerate cognitive decline. Conversely, supportive connections promote healthy neural pathways, enhance emotion regulation, and build cognitive resilience.

Additionally, this article incorporates principles such as mindfulness and the understanding of impermanence, highlighting their roles in cultivating adaptive neural states and improving interpersonal attunement. This, in turn, contributes to a neurologically robust and fulfilling life.

1. Introduction: Unraveling the Neural Correlates of a Flourishing Life

The pursuit of understanding human well-being has long captivated researchers across disciplines. The Harvard Study of Adult Development, an unprecedented 85-year longitudinal investigation, offers a unique empirical foundation for this quest. Initiated in 1938, this study has meticulously tracked the lives of 724 young men, their spouses, and over 2,000 of their descendants, employing a rich array of psychological, medical, and, more recently, biological and neuroimaging methodologies. As the fourth director, Robert Waldinger, M.D., emphasizes a consistent and profound finding: the quality of one's relationships is the single most significant determinant of health and happiness throughout the lifespan (Waldinger & Schulz, 2023).

From a neuroscientific perspective, this enduring observation raises critical questions. The study, an unprecedented 85-year longitudinal investigation, provides a unique empirical foundation for this quest. Initiated in 1938, it has meticulously tracked the lives of 724 young men, their spouses, and over 2,000 of their descendants, employing a rich array of psychological, medical, and, more recently, biological and neuroimaging methodologies.

To bridge the sociological and psychological insights of the study with contemporary neurobiological understanding, a framework is proposed wherein social interaction is viewed not merely as a behavioral phenomenon, but as a fundamental modulator of brain structure, function, and resilience. We will explore how relational dynamics influence key neurobiological systems, including stress response pathways, emotion regulation networks, and cognitive aging processes, further augmented by contemplative practices.

2. The Neurobiology of Social Connection and Stress Regulation

The Harvard study's central revelation—that warm, supportive relationships are paramount for health and longevity—finds a compelling explanation in the neurobiology of stress. Humans are inherently social animals, a trait likely shaped by evolutionary pressures favoring group cohesion for survival and gene propagation. Consequently, social isolation or perceived threat within social contexts can activate profound physiological stress responses.

2.1 Allostatic Load and Neuroinflammation

When faced with stressors, the body's primary response involves the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), resulting in the release of stress hormones, including cortisol and catecholamines. This "fight or flight" response is adaptive in acute situations, preparing the organism for immediate threats. However, the Harvard study suggests that in the absence of adequate social buffering, individuals may remain in a state of chronic low-level activation of these systems.

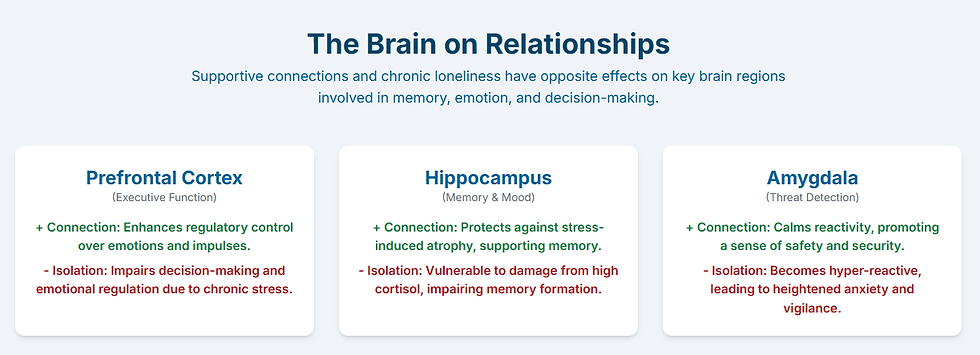

This sustained physiological arousal, referred to as allostatic load, has detrimental effects on various bodily systems, including the central nervous system, specifically the brain. Elevated and prolonged cortisol exposure can lead to neuroinflammation and structural changes in critical brain regions (Doyle & Pachankis, 2024). Specifically, the hippocampus, vital for memory formation and mood regulation, is highly vulnerable to chronic stress-induced atrophy and impaired neurogenesis. Similarly, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, working memory, and emotion regulation, can experience reduced synaptic plasticity and altered connectivity under conditions of chronic stress.

Good relationships, conversely, act as powerful stress buffers. The act of sharing worries or receiving support from a trusted individual can rapidly downregulate the HPA axis and SNS activity, allowing the body to return to a state of homeostatic equilibrium. This physiological calming, experienced as a reduction in heart rate and muscle tension, prevents the accumulation of allostatic load and mitigates the pro-inflammatory effects of chronic stress hormones on the brain.

2.2 Emotion Regulation and Neural Circuitry

The ability of good relationships to serve as "emotion regulators" is a key neurobiological mechanism. Emotion regulation involves complex interactions between subcortical limbic structures, particularly the amygdala (involved in fear and threat processing), and top-down control exerted by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) (Number Analytics, 2025a). In stressful situations, the activity of the amygdala often increases, triggering physiological arousal. However, effective emotion regulation, often facilitated by social support, involves the PFC inhibiting or modulating amygdala responses.

The study's observation that individuals undergoing stressful medical procedures maintain greater physiological equilibrium when holding someone's hand provides a compelling example. This suggests that interpersonal connection activates neural pathways associated with safety and reward, potentially involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), which are implicated in social cognition, empathy, and emotional appraisal. This activation can dampen threat-related signals from the amygdala, leading to a more regulated physiological state. The exchange of positive emotions within good relationships further reinforces these adaptive neural circuits, promoting a state of neurophysiological balance that supports overall health.

3. Relationships, Brain Health, and Cognitive Aging

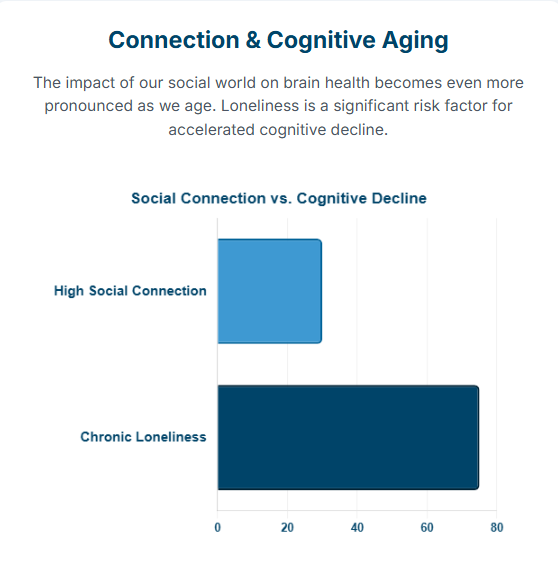

The Harvard study's findings extend beyond general health to directly implicate relationships in cognitive aging. The observation that secure connections in late life correlate with slower brain decline, while loneliness is associated with more rapid cognitive deterioration, points to a direct neurological link (Number Analytics, 2023).

Chronic stress, as discussed, contributes to neuroinflammation and reduced neurogenesis, which are known factors in age-related cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases. Conversely, supportive social environments may promote synaptic plasticity and neural network integrity. Engagement in meaningful social interactions provides cognitive stimulation, potentially enhancing cognitive reserve—the brain's ability to cope with pathology through more efficient or flexible neural networks.

Furthermore, social isolation is a significant risk factor for depression and anxiety, conditions known to be associated with structural and functional changes in brain regions critical for memory and executive function. The protective effect of relationships on brain aging likely involves multiple pathways:

Reduced chronic stress: Lower allostatic load preserves neural integrity.

Enhanced neurotrophic factors: Social engagement may promote the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), crucial for neuronal survival and plasticity.

Cognitive engagement: Social interaction demands cognitive processes like theory of mind, empathy, and communication, which can maintain neural activity and connectivity.

Improved health behaviors: Individuals in supportive relationships may be more likely to engage in healthy lifestyle choices (e.g., exercise, balanced diet, adherence to medical advice) that indirectly benefit brain health.

4. Contemplative Practices and Neuroplasticity: An Ancient Perspective

The integration of ancient philosophies, such as Zen, Taoism, Stoicism, and Vedanta, invites us to let go of illusions, embrace impermanence, and live with clarity, balance, and purpose in the present moment. This perspective on well-being becomes even more intriguing when examined through the lens of neuroplasticity. Practices like mindfulness offer a framework for developing adaptive cognitive and emotional states, which can lead to measurable changes in brain structure and function.

Zen Philosophy: Stillness in Motion

Taoism: Flowing with the Way

Stoicism: Inner Fortress of Reason

Vedanta: The Self Beyond the Self

|

4.1 Mindfulness and Brain Reconfiguration

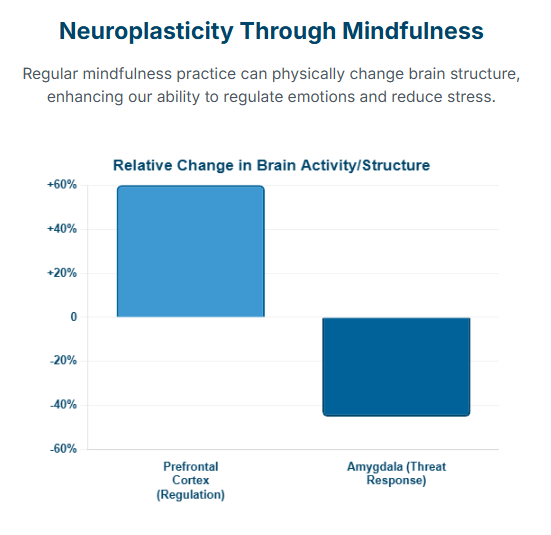

Mindfulness, defined as "paying attention in the present moment without judgment," is a core practice. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that regular mindfulness meditation can induce neuroplastic changes in several key brain regions (Number Analytics, 2025b):

Increased cortical thickness in the prefrontal cortex: Associated with enhanced attention, executive control, and emotion regulation.

Reduced amygdala volume and reactivity: Indicating a decreased propensity for automatic fear and stress responses.

Increased gray matter density in the hippocampus: Suggesting improved memory and emotional processing.

Changes in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and insula: Regions involved in interoception (awareness of bodily states) and self-regulation.

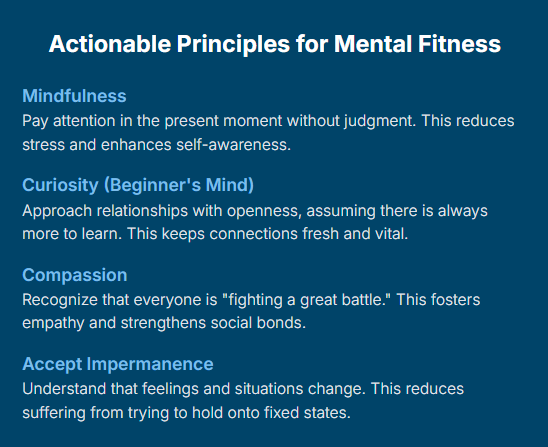

These changes align with the study's emphasis on emotion regulation and stress reduction. By training attention and non-judgmental awareness, mindfulness practices enable individuals to observe their internal states (e.g., annoyance, worry) without being overwhelmed by them, thereby preventing prolonged activation of stress pathways and fostering a more resilient neural landscape.

4.2 Impermanence, Cognitive Flexibility, and Acceptance

The concept of impermanence (Anicca)—the understanding that everything is in a constant state of flux—has profound implications for neurocognition. Our brains often seek predictability and stability, and a rigid adherence to fixed views can contribute to cognitive inflexibility and emotional distress. Embracing impermanence can reduce the suffering we inflict on ourselves by letting go of attachments to how things "should" be.

From a neurological standpoint, this practice may enhance cognitive flexibility, the ability to adapt thinking and behavior in response to changing situations. This is primarily mediated by the prefrontal cortex and its connections to other brain regions (Frontiers Research Topic, 2020; Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2024). By regularly observing the transient nature of thoughts, emotions, and external circumstances, individuals may strengthen neural pathways that support adaptive reappraisal and reduce the cognitive rigidity associated with rumination and anxiety. The acceptance of life's "unsatisfactoriness" and the willingness to "cling less tightly to our preferences" can reduce the neural load associated with constant striving and resistance, promoting a state of greater mental ease.

4.3 Compassion, Beginner's Mind, and Social Cognition

Its emphasis on compassion and the "beginner's mind" ("In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities; in the expert's mind there are few") directly relates to social cognition and interpersonal neurobiology. Cultivating compassion involves activating neural circuits associated with empathy, such as the anterior insula and temporoparietal junction (TPJ) (Mental Health Academy, 2024; Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 2013). This fosters a more prosocial orientation, enhancing the quality of relationships.

The beginner's mind encourages a non-judgmental, open curiosity towards others, even those we think we know well. This practice can stimulate neural networks involved in novelty detection and attentional processing, preventing the automatic, habituated responses that can lead to relational stagnation. By actively seeking "what's here right now that I have not noticed before," individuals engage their default mode network (DMN) in a more adaptive way, shifting from self-referential rumination to an outward-facing, curious engagement with the social world. This continuous learning and adaptation within relationships contribute to sustained neural vitality and relational depth.

5. Future Directions and Clinical Implications

The convergence of findings from the study and neuroscientific principles opens several avenues for future research and clinical application:

5.1 Research Directions

The Neural Underpinnings of Enduring Well-being: Future phases of the Harvard Study could incorporate more extensive longitudinal neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI, DTI) to directly track changes in brain structure and function in relation to relationship quality and stress biomarkers over decades.

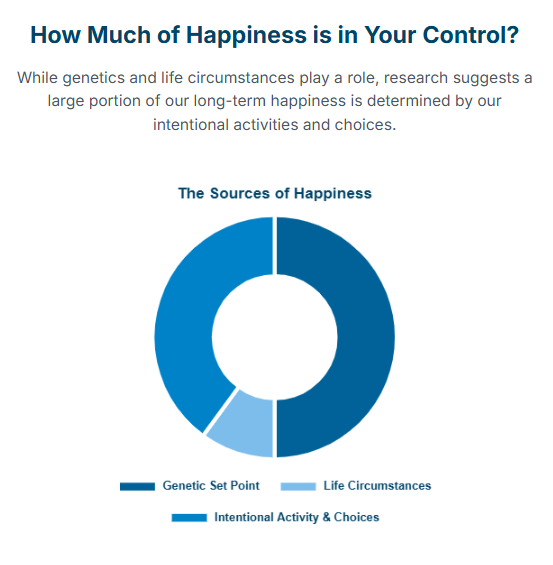

Genetic and Epigenetic Influences: Further investigation into how genetic predispositions (e.g., temperament, as suggested by Lyubomirsky's 50% "set point") interact with relational experiences and stress to influence neural development and aging. Epigenetic studies could explore how early childhood relationships or adult relational quality lead to lasting changes in gene expression related to stress response and brain health.

Biomarkers of Social Fitness: Identifying specific neurobiological biomarkers (e.g., inflammatory markers, neurotrophins, functional connectivity patterns) that correlate with different levels of "social fitness" and predict long-term brain health outcomes.

Intervention Studies: Designing and implementing randomized controlled trials to assess the efficacy of relationship-focused interventions (e.g., couples therapy, social skills training, community engagement programs) and mindfulness-based interventions on neurobiological markers of stress, emotion regulation, and cognitive function.

5.2 Clinical Implications

Social Prescribing: Healthcare systems could integrate "social prescribing" initiatives, formally recommending and facilitating engagement in community groups, volunteer activities, or social support networks to improve mental and physical health outcomes, particularly for individuals at risk of loneliness or chronic stress-related conditions.

Relationship-Focused Therapies: Psychotherapeutic approaches could more explicitly incorporate the neurobiological benefits of healthy relationships, guiding patients to actively cultivate supportive connections and develop skills for navigating relational challenges, thereby reducing allostatic load and promoting neural resilience.

Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Expanding the integration of mindfulness and compassion-based practices into clinical settings for a wide range of conditions, recognizing their capacity to foster neuroplastic changes that enhance emotion regulation, reduce stress, and improve interpersonal functioning.

Public Health Campaigns: Developing public health campaigns that emphasize the profound neurobiological benefits of social connection, shifting societal focus from purely individualistic pursuits to the cultivation of relational well-being as a cornerstone of health.

6. Conclusion

The Harvard Study of Adult Development, through its unparalleled longevity and depth, provides compelling evidence that good relationships are foundational to a well-lived life. From a neuroscientific perspective, this is not merely a psychological truism but a reflection of deep-seated biological and neurological realities. High-quality social connections serve as potent regulators of the stress response, fostering adaptive neuroplasticity, preserving cognitive function, and mitigating the detrimental effects of allostatic load and neuroinflammation on the brain.

Furthermore, the wisdom of contemplative traditions offers practical, trainable approaches—such as mindfulness, the acceptance of impermanence, and the cultivation of a beginner's mind—that align with and potentially enhance these neurobiological benefits. These practices promote emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and prosocial behaviors, all of which contribute to a more resilient and adaptable brain. Ultimately, the synthesis of insights from the study and neuroscience underscores that investing in our relationships is not just a lifestyle choice but a strategy for optimizing brain health and achieving enduring well-being across the entire human lifespan.

References

Doyle, F. M., & Pachankis, J. E. (2024). Social exclusion and psychopathology in LGBTQ+ communities: a neuropsychosocial review. Frontiers in Sociology, 10, 1638766.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. (2013). Structural basis of empathy and the domain general region in the anterior insular cortex.

Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. (2024). Measuring cognitive flexibility: A brief review of neuropsychological, self-report, and neuroscientific approaches.

Frontiers Research Topic. (2020). Maintain that Brain - Protecting and Boosting Cognitive Flexibility.

Mental Health Academy. (2024). The Neuroscience of Empathy: Implications for Therapy.

Number Analytics. (2023). Are social isolation and loneliness associated with cognitive decline in ageing?

Number Analytics. (2025a). The Neuroscience of Emotional Regulation.

Number Analytics. (2025b). The Neuroscience of Meditation: An fMRI Perspective.

Waldinger, R. J., & Schulz, M. L. (2023). The Good Life: Lessons from the World's Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. Simon & Schuster.

About Dr. David L. Priede, MIS, PhD

As a healthcare professional and Brain Researcher at BioLife Health Research Center, I am committed to catalyzing progress and fostering innovation. With a multifaceted background encompassing experiences in science, technology, healthcare, and education, I’ve consistently sought to challenge conventional boundaries and pioneer transformative solutions that address pressing challenges in these interconnected fields. Follow me on Linkedin.

Founder and Director of Biolife Health Center and a member of the American Medical Association, National Association for Healthcare Quality, Society for Neuroscience, and the American Brain Foundation.